Despite acknowledging Georgia’s independence a year prior, in 1921 Russian forces overtook the country, declaring it a Soviet Socialist Republic. In subsequent decades, repression of political dissidents was commonplace, reaching a climax in 1937-1938, during what is known as “Stalin’s Purge,” in which at least 30,000 Georgians were imprisoned or killed. In 2019, the first mass grave in Georgia of people killed during this time was discovered. In this interview, the Coalition speaks with Anton Vacharadze, the Director of Archives and Soviet Studies Research at the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), which received a 2020 Project Support Fund to create an online memorial and organize public discussions to commemorate and bring awareness to the site.

Can you please give a brief history of Soviet repressions in Georgia? And how IDFI works to document and share that history?

Part of the Russian Empire since 1801, Georgia declared its independence in 1918. A year later, its citizen elected a Social-Democratic government (FDR), and in 1920 Georgia’s independence was formally recognized by Russia. Despite this, under the pretense of supporting “peasants and workers,” Russian forces took the Georgian capital Tbilisi in 1921 and declared it the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Repressions started immediately. In March 1921, most influential members of the Government of FDR were forced to leave the country. Those who stayed were subjected to repression, first detained in prisons and then deported to various parts of Russia. Over the next several years, resistance groups were established but its members were consistently arrested and sentenced to death. The exact number of casualties and victims of the purges remains unknown, but approximately 3,000 died in fighting. The number of those who were executed during uprisings or in its immediate aftermath amounted to at least 7,000–10,000 people.

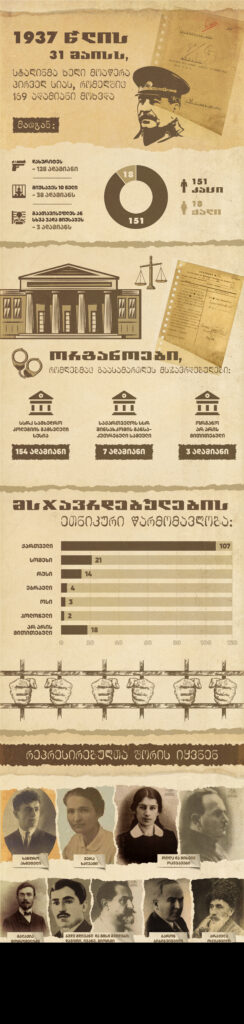

Repression reached a climax in 1937-1938 in Georgia, during what is known as “Stalin’s Purge” or the “Great Terror.” Around 30,000 people were repressed, while 3,616 were executed by Joseph Stalin’s direct order. These were the largest repressions in the Soviet Union and in Georgia, and are still being studied.

Over the next several decades, there were repeated incidences of Soviet repression and violence toward Georgian protestors and resistance generally, with many losing their lives. On April 9, 1989, a peaceful anti-Soviet demonstration for succession from the Soviet Union was met with deadly force by the Russian Army. The day is now remembered as the Day of National Unity, and two years after the tragedy, which killed 21 people, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia proclaimed Georgian sovereignty and independence from the Soviet Union.

In order to disseminate truthful information about these tragic events, IDFI carries out archival research, collects documents and oral histories, and studies databases available online. Based on this research, IDFI creates articles, publishes books, develops videos, etc., in order to memorialize those lost and share their experiences. For a complete list of our activities, please visit here.

In 2019, the first mass grave in Georgia of people who were executed in 1937-38 during Stalin’s reign there was discovered. Can you speak about the significance of this?

The discovery of the mass graves is a very important event for Georgia. In general, the studies of the stories of repressed persons, their proper commemoration and immortalization is an urgent issue in the post-Soviet region. In many countries, on execution and burial sites, there are memorials and educational programming around the sites. These places have a key role in the formation of the collective memory of the countries and the rethinking of their totalitarian past.

The mass grave discovered in Georgia is the first discovery of its kind in the country, which requires appropriate attention from the state. Moreover, this issue is very important for the descendants of victims. These families require proper commemoration of their ancestors and for this, they need scientific evidence that particular bodies belong to their ancestors. They also need collaboration between the local Christian and Muslim communities to organize a joint memorial and ensure the proper commemoration of all of the victims.

It will also be important to locate other graves, which requires extensive archival research, considerable human resources – including foreign experts who are more experienced in this field – and significant financial resources. Currently, this process is suspended due to the pandemic. Once we are able to resume, government support will be crucial for this effort, as it would be very difficult for the civil sector alone to accumulate such big financial recourses for this purpose. For this, it is important for civil society to focus on advocacy campaigns to increase both public awareness as well as the government’s interest in studying and commemorating the mass graves of the victims of political repressions.

In 2020, you were awarded a Project Support Fund by the Coalition to create an online memorial and organize public discussions to commemorate and bring awareness to the site. Can you describe the project in more detail?

In 2020, IDFI became a member the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience and received funding from the Coalition for the project “Commemoration of the First Mass Graves of the Victims of the Soviet Regime Discovered in Georgia.” The finding of the mass grave in Georgia poses many challenges, including bridging differences between local Muslim and Christian populations regarding religious ceremonies conducted at the site, as bodies of both Muslims and Christians are in the grave. Considering this, IDFI’s project aims to enhance dialogue between local Muslim and Christian communities to foster social cohesion and understanding, raise public awareness about the mass grave, and attract the government’s attention to the issue.

To that end, we have conducted a number of activities with our Project Support Fund Grant, including an online discussion about the mass grave, which was attended by representatives from the media, civil society and academia. The TV channel Rustavi 2 made a documentary film about this issue, featuring IDFI. In addition, in February 2021, IDFI held an online conference, “Discovery, Archaeological Research and Commemoration of the Mass Burial Sites of the Victims of the Soviet Regime – International Experience,” which explored the field of searching, discovering and identifying graves and remembrance sites. Finally, to raise public awareness about the mass grave discovered in Georgia, IDFI conducted interviews with experts in the field and published two articles – “Online Discussion on the Issues Related to the First Mass Grave of the Victims of the Soviet Regime in Adjara” and “Online Conference – Discovery, Archaeological Research and Commemoration of the Mass Burial Sites of the Victims of the Soviet Regime – International Experience” about the importance of the issue and the related activities carried out by the organization.

To that end, we have conducted a number of activities with our Project Support Fund Grant, including an online discussion about the mass grave, which was attended by representatives from the media, civil society and academia. The TV channel Rustavi 2 made a documentary film about this issue, featuring IDFI. In addition, in February 2021, IDFI held an online conference, “Discovery, Archaeological Research and Commemoration of the Mass Burial Sites of the Victims of the Soviet Regime – International Experience,” which explored the field of searching, discovering and identifying graves and remembrance sites. Finally, to raise public awareness about the mass grave discovered in Georgia, IDFI conducted interviews with experts in the field and published two articles – “Online Discussion on the Issues Related to the First Mass Grave of the Victims of the Soviet Regime in Adjara” and “Online Conference – Discovery, Archaeological Research and Commemoration of the Mass Burial Sites of the Victims of the Soviet Regime – International Experience” about the importance of the issue and the related activities carried out by the organization.

As for the online memorial, in May 2021, IDFI will launch a special website dedicated to preserving and sharing the history of the mass graves, which will include articles, visualizations, videos, and archival materials. IDFI hopes that the site will prompt the government to erect a physical memorial at the place of the discovery.

How did the project allow your community to engage with this topic in a way they hadn’t before? As you see it, what were the biggest outcomes in terms of public engagement and healing?

One of the major activities within the frame of the project was the online discussion between the representatives of the local Muslim and Christian communities – a conversation that does not often take place in this context. One of the primary reasons for holding the discussion was to foster understanding between the two communities and try to reach a resolution regarding the religious practices that might take place at the grave. It was also an opportunity for each side to air concerns in a safe space. For instance, the Muslim community raised its voice regarding concerns about how the state will handle the study and commemoration of the discovered graves and also its fear that the Orthodox Church may weaponize this issue.

The involvement of multiple parties in the discussion was also important and groundbreaking. Representatives of civil society, religious organizations, central and local governments, descendants of the repressed, experts and activists all participated in the discussion, which demonstrated that different social groups have an interest in this topic. Since this process was financially supported by the Coalition and Sida, its profile was also enhanced.

IDFI invited leading international experts from countries that have experience in discovering, studying and commemorating mass graves at the highest level. Through this, the organization demonstrated the importance of the issue to the government. IDFI hopes that the central, as well as local government, will pay more attention to this issue to start working on studying and commemorating the discovered graves in the near future.

How will the project advance democracy in the country more generally? What role can such memorials play in such contexts?

Stalinist sentiments are significantly higher in Georgia than other post-Soviet countries, which is a challenge to the democratic transition of the country. The prevalence of Stalinist sentiments in the country indicates that the rethinking of the Soviet past has not been accomplished here. Rethinking of the Soviet totalitarian past as well as raising public awareness about the crimes of the non-democratic, totalitarian regime play an important role. For this reason, IDFI considers it of paramount importance to start the process of de-Stalinization and de-Sovietization through in-depth archival research, enhanced memory studies, implementation of effective memory politics, proper commemoration of the victims of communism and enhancing the openness of state archives for studying the Soviet past.

At the places of the discovery of mass graves of the victims of totalitarian regimes, in many countries (in Eastern Europe, essentially) large-scale studies are being carried out to identify the discovered bodies and memorial complexes are being erected for commemorating the victims. Such symbolism plays an important role in constructing a collective memory about the repressions and serves as a preventive measure against the re-emergence of similar regimes in the future. For this reason, IDFI advocates for the study of the discovered graves and their proper commemoration. If the memorial complex is erected at the place, educational tours can be organized there which would raise public awareness about the crimes of the Soviet regime.