A Conversation Between Prison Public Memory Project (USA) and Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project (Australia)

Bonney Djuric OAM

Founder/Director, Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project

Parramatta, Australia

www.pffpmemory.org.au

Tracy Huling

Founder/Director, Prison Public Memory Project

Hudson, NY and Pontiac, IL, USA

www.prisonpublicmemory.org

Lily Hibberd (Moderator)

Artist and Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project collaborator

ARC DECRA Research Fellow University of New South Wales, Australia

LH: In 2012, two kindred Sites of Conscience were simultaneously yet independently established 10,000 miles apart: Prison Public Memory Project in the United States (PPMP) and Australia’s Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project (PFFP MP). Over the past few years we have become increasingly aware that we share a common endeavor to engage, activate and ameliorate public perceptions of institutional welfare and incarceration in our respective cultures. There are striking parallels between the layered institutional histories of Hudson and Parramatta, as emblems of the intwinement of penal and welfare systems in colonial nations and the contemporary systemic forgetting that women and girls underpin this paradoxical system of punitive care. As a result, we both strive for an ethos of community activism and the amendment of official, albeit marginalizing, public histories through artistic interpretation. We also seek to make a legitimate and empowering place for women’s experiences of these institutions, which remain otherwise side-lined.

There are however a number of differences between us. Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project is an extension of the Parragirls’ collective of former residents from Parramatta Girls Home, who have campaigned for the preservation of the site as witnesses to the violations that took place there, more than forty years after its forced closure in 1974. Prison Public Memory Project’s mission, built on the experience of its founder with both prisoner receiving and sending communities, is to engage people from all walks of life in conversation, reflection and learning about the complex roles of prisons in communities and society. The Site of Conscience collaborates closely with “prison host” communities surrounding operative prison sites, most recently in Pontiac, Illinois, alongside their first location in Hudson, New York.

The following dialogue between the sites’ two founding directors — Prison Public Memory Project’s Tracy Huling and Parramatta Female Factory Precinct’s Bonney Djuric — offers unique insights into what they have learned or would like to learn from each other, as well as a detailed look at the transnational significance of these intensely place-based, site-specific institutional memory projects.

TH: Bonney, I’ll be forever grateful to the Coalition for introducing me, shortly after Prison Public Memory Project became a member, to you, Lily Hibberd and the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project. I treasure the deep conversations we’ve had over the last couple of years about our two projects, so far away from each other in miles and culture, but with amazing parallels both in time and content. Also, finding out that we had faced similar challenges in a couple of key areas was both confirming and comforting. When we began in the US, we were breaking new ground here and while that’s always exciting, it can be lonely.

BD: It’s been very encouraging knowing that others are also tackling the history, memory and lived experience of the institution. After all, it’s people that matter. Given that these institutions were used as a means of social control, it’s important that those with a direct experience have a chance to engage in how they are remembered, how this history is interpreted and how these places are used in the future.

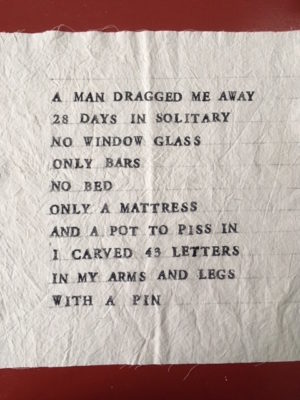

TH: Yes, it is… To this point — and using Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project as a model for how to effectively engage and empower former residents of these institutions through creative projects — we’ve just launched our first art-based project with a former resident of the New York State Training School for Girls (1904 – 1975), once the largest juvenile detention center for girls in the United States. In April this year, we exhibited one outcome of this project — a book of photographs of a cloth-based artwork-in-progress — at a national symposium, “Incarcerating Girls and Women: Past & Present,” sponsored by the School of Criminal Justice at the State University of New York in Albany, NY. The final project will be exhibited in December at the Davis/Orton Gallery in Hudson, NY.

A couple years ago, it became clear to me that some of the women we were in touch with who had been incarcerated as children at the Training School in Hudson, NY had not had an opportunity to process very painful experiences there and within their families. As adults these women lacked support systems, and I began questioning whether it was wise to conduct oral histories with them. We had used oral history quite successfully to engage former staff at the Training School and one of the former residents. But there were several other former residents that we wanted to work with and talking about their experiences was either not possible for them or excruciating.

It was at that time that you and Lily came into my life, so to speak, and began sharing your own successes and failures with the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project. I saw that there were options beyond oral history to engage the women in “telling their own histories” of the Training School. Two pieces of advice that you and Lily provided were particularly helpful: 1) to focus on creative projects that allowed the women to work on an individual project or one piece of a project by themselves and 2) to be very careful that the artists who we invited to work with ‘the survivors’ were truly concerned about the women and their lives and not overly concerned with gaining their own fame and fortune.

We are very, very fortunate to have a highly skilled and very caring artist educator, Maureen McNeil, working on our new project with former Training School resident Luz Minerva Muniz. I just met with Luz myself when I was back in New York in April and I was so happy she reported feeling terrific about the art-based project, the artist and herself. For the first time, Luz feels she can and wants to share her experiences and thoughts about those experiences with others. This is both a giant step for Luz and for Prison Public Memory Project as this experience will inform a larger project we want to develop involving more formerly incarcerated women. I wonder if you could share some more of your own history and thinking about these kinds of projects focusing on how and why your projects evolved the way they did.

BD: I have always been an artist. As a teenager I longed to study at the National Art School, but ended up here at the Parramatta Girls Home instead. Some forty years later, however, I finally realized this dream and in doing so, revisited the crossroads where my life had taken a different path. It was time to return, time to ask questions I never asked when young. It was a solitary journey which over time became a shared journey as others made contact through a website I established. At first there were reunions and gatherings. We all wanted to revisit the site. We all had questions and a desire to have our experiences validated. We had lived our lives silenced and shamed; it was time to speak up.

Outsiders often talk about oral history, but it wasn’t oral history that each of the women shared with me on first contact or subsequently. It was a conversation between people each seeking some sort of affirmation that what we did remember, feel and experience was indeed real. We don’t react with surprise, shock or horror, nor display signs of pity or voyeurism when we listen to each other. We know these things did happen. It may appear we have solidarity, but that’s only an illusion imposed from the outside. For the most part we remain as isolated and alone as we were when in the institution. This makes for a very difficult task in bringing people together as a collective to engage with the site, its past, present and future. The idea of an open-ended arts-based Memory Project appealed as a way forward to bear witness to the history, heritage and legacy of this site.

Tracy, you mention how difficult and even excruciating it is for former residents to speak about their experiences. I agree, the exchange only comes over time when trust is built and the right sort of people are there to support and guide the process. For arts workers, it’s crucial that they put their creative ego aside to open up possibilities for others. I’d add that too often what we do is misconstrued as art therapy. It is not. Instead, I liken what we do to the tradition of quilt making, where individuals create a patch that is sewn together with others to make a whole. It is always a work in progress that can have another patch added.

TH: I think the quilt metaphor is very apt. None of the women’s experiences is exactly the same. Each provides a unique picture of the complex history of these total institutions but when viewed together larger patterns emerge.

LH: Art, like a quilt, is an interface between disparate cultures and sometimes conflicting world views. It has the capacity to elevate ideas and experiences that would otherwise be overlooked or misunderstood. While art has the power to disabuse truth, it also makes space for those whose stories have been marginalized or denied. Literary, visual and performing arts are at liberty to redefine the boundaries of official history and to invent new forms of art to break apart the walls that confine public memory. Art has played an important role for both Parramatta Female Factory Precinct Memory Project and the Prison Public Memory Project. First, as a way to bring people together; second, as a means to record and translate difficult and traumatic experiences; third, as a way of communicating intangible and marginalized memories about institutionalization or incarceration; and fourth, to give political and social presence and agency to the people who passed through or remain in these places. Looking back from the distant future, it is also probable that people will ultimately look to these artworks to tell the whole story, to find her-story.