Through its Methodology and Practice department, the Coalition offers a range of trainings and consultations to help museums, historic sites and other cultural organizations engage visitors in ever relevant and sustainable ways. Led by Sarah Pharaon, a consultant on the Coalition’s Methodology and Practice team, the department recently completed a robust revitalization project with member Pearl S. Buck International (PSBI).

Pearl S. Buck International celebrates the life and legacy of author Pearl S. Buck, who was the first American woman writer to win both the Nobel Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for Literature. As the owner of Buck’s historic home in rural Pennsylvania, PSBI had long used the site to educate visitors about Buck’s contributions to literature, but today, with the Coalition’s help, they have reinvigorated their programs to include Buck’s robust legacy as an advocate for social justice – particularly her support for racial and gender equity as well as the rights of children.

Below Sarah speaks with the Coalition about the project and how historic houses can speak to contemporary challenges.

Can you tell us a bit about Pearl S. Buck International and how they initially became involved with the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience?

The Coalition was first contacted by the PSBI leadership team in 2016 because they had heard about our work and wanted to discuss membership. That is when I first began to understand that Pearl S. Buck is so much larger than The Good Earth, her most famous book. Building on her legacy, PSBI focuses on programming around international cultural exchange, children, education, wellbeing, and leadership; and they also own the home where Buck and her husband lived. The historic house is located on Green Hills Farm in a rural part of Pennsylvania and is almost perfectly preserved from the author’s time, which means it contains a remarkable collection of artifacts and manuscripts that offer an unprecedented look into her life.

Shortly after this introduction, the Coalition began a multi-faceted two-year project that changed the direction of the historic house with a view towards social justice and the site’s longterm sustainability. What were the main challenges facing the site that led PSBI to initiate this project?

In general, historic house museums can struggle to maintain funding, attendance, and to really play essential roles in their communities. PSBI was at a crossroads with this site — and with how to make the house and Buck’s belongings represent her mission and values in a more holistic and direct manner. They knew opportunities were being missed. For instance, the site was the home of a female author, which makes it part of a very small and important subset of all historic houses in the United States — and yet most people who had visited the house and taken the previous tour were not encouraged to reflect on that or the fact that Buck was an advocate for gender equity, as well as for racial equality and the rights of differently-abled children. They left knowing her as primarily the author of The Good Earth.

Our charge, then, was not only to update their tour to incorporate Buck’s advocacy work, but also to make it an experience that would energize and activate a general audience to further Buck’s legacy. How could the organization capitalize on the unique space to support its larger social justice work? How do you take a traditional historic house tour and make it heavily experiential — something that touches people on a personal level? How do you promote action among visitors and surface stories of Buck’s work that would surprise and provoke visitors?

The Coalition led this effort, which was funded by the Barra Foundation. To begin, we conducted a lengthy evaluation effort that included research, a needs assessment, and discussions with focus groups. Only when this was completed did the creative process of designing the tour begin. We worked as a three-person team of consultants — with Night Kitchen Interactive, an exhibit design firm, and a writer Sandy Lloyd. The three of us collaborated with Marie Toner, the curator at PSBI and senior staff members. We also brought in a group of scholars and other colleagues from two Coalition members, the Tenement Museum in Manhattan, NY and the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, CT.

How does the new tour compare with the old?

The new tour, which opened in September 2018, is called Taking Action. While the previous house tour focused on Buck’s life in the house, the architectural changes, the property, and of course on the desk and typewriter where she wrote The Good Earth, the new tour focuses on Buck’s social justice work, her avenues of advocacy for children, as well as her work on race relations. Buck was a member of the NAACP at a time when most white women were not. The tour also discusses her role as a global human rights activist looking at East and West relations as well as her work around gender discrimination. This activism evolved from her experiences being raised by missionary parents in China, her role as a mother to a differently-abled child, and her experiences as a lauded female writer in a male-dominated profession.

With this information, we instituted and built in more sensory-based experiences. We added audio and video materials in organic ways, trying to be cognizant of the fact that the collection is 97% intact. We needed to modernize the interpretative approaches by adding media in ways that were respectful of the fabric of the house.

Most importantly, the tour is dialogic in its foundations. Visitors — from the moment they are greeted by facilitators — are engaged in conversation and not only about the contents of the house and Buck’s life, but with each other. The tour is meant to be led by a facilitator but it is flexible to the interests and needs of any group of visitors. It is meant to build on whatever knowledge base and personal experience that group of visitors has.

How did you prepare the staff to facilitate this sort of dialogic and experiential tour?

In addition to conducting research and designing the tour, we had a long process of training staff. All of the facilitators at PSBI are volunteers — and they are by far the most passionate and dedicated group of volunteers I have seen at a historic site. Some are adoptees that came through Buck’s adoption program. Some of the volunteers knew Buck personally before she passed away. They are the warmth and lifeblood of the institution.

Honestly, because of their interest and passion, I was nervous to ask them to change what they were doing and to facilitate a different kind of experience. When you are that passionate about your work, change is sometimes difficult, but they stepped up to the plate in a way that exceeded all expectations. We did extensive training with the volunteers and staff in dialogue facilitation for the new tour content. These volunteers were also vital in helping us develop the new dialogic questions that we are asking at the site. They helped create the content and are invested in its success — which is crucial to the site’s mission and longevity.

What is your favorite dialogic element of the tour, and how do visitors, staff and volunteers engage in it?

I am really proud of the large library. It is where Buck’s desk is located as well as the typewriter where she wrote The Good Earth. We found during the evaluation that people wanted more of Buck’s words in the house — both written and spoken — as she is mostly known as an author. We wanted to use the large library as a space for visitors and community members to talk about issues of race in America today. Collaborating with Night Kitchen, we used theatrical scrims to cover some of the bookshelves. As you enter the space, the books just look like they are on the bookshelf. Then, after relaying some content, the facilitator presses a button and the lighting changes so that visitors hear the sound of a typewriter, and Pearl S. Buck’s words on race appear, overlaid on top of the bookshelves. These quotes are used in a dialogic exercise. We ask visitors to select a quote that resonates with them and the conversation grows from there. Ideally, the tour can model for participants how we as a people or a nation can listen to each other again — in ways that we seemingly have forgotten.

I am really proud of the large library. It is where Buck’s desk is located as well as the typewriter where she wrote The Good Earth. We found during the evaluation that people wanted more of Buck’s words in the house — both written and spoken — as she is mostly known as an author. We wanted to use the large library as a space for visitors and community members to talk about issues of race in America today. Collaborating with Night Kitchen, we used theatrical scrims to cover some of the bookshelves. As you enter the space, the books just look like they are on the bookshelf. Then, after relaying some content, the facilitator presses a button and the lighting changes so that visitors hear the sound of a typewriter, and Pearl S. Buck’s words on race appear, overlaid on top of the bookshelves. These quotes are used in a dialogic exercise. We ask visitors to select a quote that resonates with them and the conversation grows from there. Ideally, the tour can model for participants how we as a people or a nation can listen to each other again — in ways that we seemingly have forgotten.

Every cultural organization has its own context and elaborate history. How do you tailor the Coalition’s methodology and training to each site?

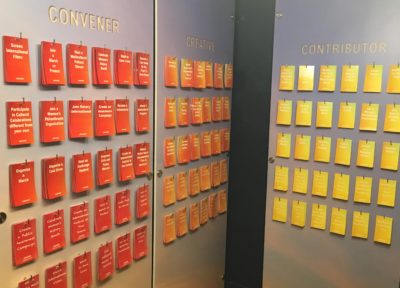

The Coalition’s work is always as site-driven and as grassroots as possible. As members join the Coalition, they commit to the pillars of the Coalition’s practice: 1) connecting past to present; 2) using dialogue as a primary method of interpretation; 3) encouraging visitors to take action; 4) building programs and practices that support humane futures. Many members that join the Coalition are committed to strengthening their practice in these areas, but are already committed to the work in some capacity.

Our general approach whenever we begin a new project is to look at what a site’s unique strengths are. What parts of Sites of Conscience practice does the site already excel in? Looking at Pearl S. Buck International, they were already excelling in opportunities for involvement and their dedication to building democratic, humanitarian societies. Their goal was to better incorporate Buck’s historic house into this mission.

The site always leads a project in this way, with the Coalition coming in to bolster and provide a scaffolding of sorts — based on the experiences of our members and our work in the field for nearly twenty years now.

For more information, or to book a training, contact Sarah Pharaon at spharaon@sitesofconscience.org.