By Yolanda Chávez Leyva, Ph.D.

Director, Institute of Oral History &

The Borderlands Public History Lab

The University of Texas at El Paso

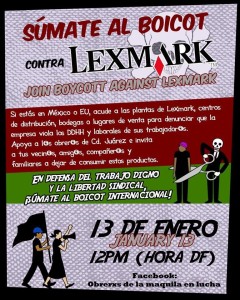

Women workers are at the forefront of what some are calling “the new labor movement in Mexico.” In a recent case, the U.S. based print company Lexmark fired about 120 striking workers at a plant in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico after the employees demanded better working conditions and a daily raise of 35 cents (USD) for experienced workers, most of whom are women. As the strike continues among those still technically employed, many women workers are surviving on donations, mostly from U.S. supporters.

Despite their financial difficulties, those on strike have continued to keep working conditions and low wages in the public eye through public actions and media outreach. Antonia Hernández Hinojos, a 45-year-old grandmother who was recently fired, is also running for the mayor of Juárez.  These women speak not only for those at Lexmark, but for all women workers in Mexico. In recent years, wages there have dropped to a historic low compared to living expenses. With the workforce now including large numbers of women with family responsibilities, women everywhere in Mexico are finding it ever more difficult to survive on low wages.

These women speak not only for those at Lexmark, but for all women workers in Mexico. In recent years, wages there have dropped to a historic low compared to living expenses. With the workforce now including large numbers of women with family responsibilities, women everywhere in Mexico are finding it ever more difficult to survive on low wages.

These are the sorts of narratives that the Borderlands Public History Lab at the University of Texas, El Paso (BPHL) works to disseminate. Just launched in January 2016, the organization will preserve and promote such borderlands and immigration histories through a variety of means, including museum exhibits, oral history projects, dialogues, public history workshops and classes. The work of the BPHL is grounded in the long-time success of the Institute of Oral History, which was established as part of the University’s Department of History in 1972, and Museo Urbano, a museum without walls celebrating its tenth anniversary this year. Both are dedicated to preserving borderlands history.

What we know from this archival work is that nothing about the ongoing labor dispute at Lexmark is new. For a century, Mexican and Mexican American women have labored in border factories with poor working conditions and low pay. Equally important, they have long endeavored to better their conditions. In November 1919, the El Paso Herald Post reported that Mexican American women working at two laundries went on strike for higher wages. The women told the Texas Industrial Welfare Commission that they needed $15-$19 per week to survive but were receiving anywhere from $4-$11 per week. Employers argued that Mexicans had a lower standard of living and could survive off lower wages than “American” women.

There have been success stories too. In 1972, 4,000 workers went on strike at Farah, Incorporated, also in El Paso, demanding representation by a union. Farah’s labor force was almost all Latino and 85% women. In addition to the strike, the women implemented a successful boycott of Farah pants. In 1974, the National Labor Relations Board ordered Farah to re-employ strikers who had been fired, permit the union, and implement a new contract that included pay raises and other changes.  In the wake of the 1972 Farah strike, a group of displaced women garment workers along with Chicana activists founded La Mujer Obrera (LMO) in 1981. For 35 years, LMO has continued to challenge the idea that Mexican heritage women are an endless source of cheap labor.

In the wake of the 1972 Farah strike, a group of displaced women garment workers along with Chicana activists founded La Mujer Obrera (LMO) in 1981. For 35 years, LMO has continued to challenge the idea that Mexican heritage women are an endless source of cheap labor.

When archived properly and made available to the public, these experiences provide guidance and insight into tackling today’s labor rights challenges. For more information, please visit:

Updates on the strikes in Juárez, see the Facebook page, Obrerxs de la Maquila en Lucha.

La Mujer Obrera website: https://www.mujerobrera.org/

The Farah Strike: Emily Hong, “Women at Farah Revisited: Political Mobilization and its Aftermath among Chicana Workers in El Paso, Texas, 1972-1992.” Feminist Studies 22 (1996).

To search the collection of the Institute of Oral History at UTEP, see https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/interviews.

All images courtesy of Yolanda Chávez Leyva